Marion Thénault shares updates on her carbon neutrality journey

Last year, freestyle skier Marion Thénault began a major project in hopes of reaching a goal very close to her heart: make it to her second Olympic Games, all while becoming one of Canada’s first carbon-neutral Olympic athletes.

One year into this journey, the freestyle superstar joins us to share how things are progressing.

RELATED: Staying carbon neutral on the road to the Olympics: a welcome challenge for Marion Thénault

How did the first year of your project go?

I’ve learned a lot. I’ve learned that quantifying carbon emissions is complex and involves several factors. It’s not easy to get concrete figures.

Are there constraints and limits to quantifying the carbon emissions of your activities?

Yes, definitely. It’s important to mention that many calculations are based on averages.

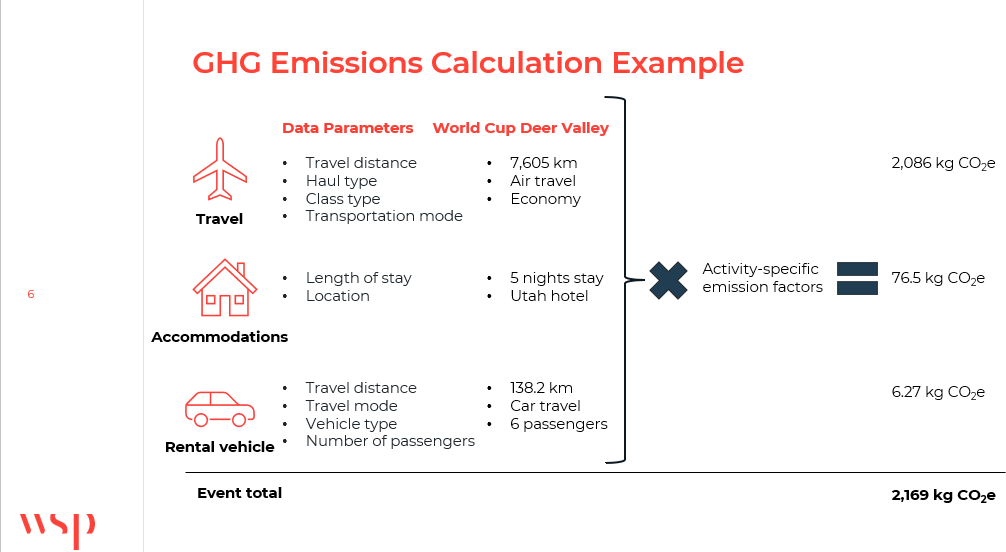

Let’s take accommodation for example: there is a database of carbon emissions for a one-night stay in a hotel in each country. For example, in Switzerland, emissions correspond to 6.5 kgCO2e/night, while in the USA, they correspond to 12.3 kgCO2e/night. This depends, among other things, on how energy is produced in that country. This is an average value for the whole country and does not take into account fluctuations from one hotel to another.

Carbon footprints vary greatly from country to country. In Quebec, we produce over 95% of our electricity using hydroelectric dams, which is very advantageous in terms of carbon footprint. However, when we travel, the same electricity consumption can have a much greater impact on our carbon footprint. One night in a hotel in Kazakhstan, where the last World Cup of the 2022-23 season took place, emits 10 times more CO2 into the atmosphere than one night in a hotel in Canada. Therefore, the destinations on the World Cup circuit have a big influence on my ecological footprint.

Our early-season training camp takes place in Ruka, Finland. Ruka Ski Resort is a carbon-neutral ski resort because of the way they produce energy, manage waste, and offset emissions. How do you quantify the carbon emissions of a day of skiing? The reports don’t go into detail about every single activity. We must focus on the broad outlines of the main factors that have the greatest impact. However, those factors that contribute significantly to the carbon footprint are also the most difficult to change. Most of my individual actions are not visible in the report. Now, I must try to understand how I can have the influence to bring about changes greater than my own individual actions.

We also made the decision not to quantify the carbon footprint of the waste I generated, as this involved weighing my garbage, compost, and recycling daily, all over the world. It was complicated, and we knew that the proportion of emissions would be minimal.

We quantified my emissions related to air travel, ground travel (train, car, bus) and accommodations when I’m at training camp and competitions.

The first year of your four-year partnership with WSP was an opportunity to quantify as precisely as possible the carbon emissions linked to your competitions. What has the data collected over the past year revealed?

Overall, 89% of my carbon emissions come from air travel. I suspected that air travel was a major contributor to my carbon footprint, but that percentage is still surprising. Air travel has a much higher footprint than any of my other activities, since my accommodations account for 9% of my carbon emissions, while just 2% is attributable to travel by car.

Your partner, the engineering firm WSP, helps you identify the various options for reducing your ecological footprint. Has their expertise had an influence on any of your choices to date?

Thanks to their expertise, WSP provides me with the information. It’s then up to me to make choices based on that information.

The phases that consume the most energy during an airplane flight are the take-off and landing. So short flights require more energy per kilometre than long flights. It’s better to take as few flights as possible to get to your destination. I avoid flying from Quebec City to Montreal at the start of a long trip. However, a trip from Quebec City to Montreal alone by car is not very advantageous in terms of carbon emissions since a car creates 12 times more emissions per passenger than a plane trip. A good alternative is the electric car, which significantly reduces carbon emissions compared with other options. In Europe, for the same distance, a train journey emits much less per passenger than the same journey by plane.

When it comes to transportation, the number of passengers is an important factor. I now know that taking the bus from Quebec City to Montreal emits 67 times less carbon per passenger than driving alone in a gasoline-powered car. Of course, these figures imply that the bus must be full, but in my experience, this is often the case. Ride-sharing services are also interesting options, since carbon emissions are divided by the number of passengers.

While it might not be quantified in the report, the WSP specialists showed me the importance of composting. Composted organic matter emits CO2 as it decomposes in the presence of oxygen and micro-organisms. Organic matter that is thrown away is sent to landfill, where it decomposes without the presence of oxygen, emitting CH4, a greenhouse gas 28 times more potent than CO2 in terms of global warming potential. Most European countries and Canada offer composting services, but this is not the case everywhere in Asia and in some US states.

Will the data you’ve collected so far be able to influence some of your choices between now and 2026?

Yes, because I understand that my actions have a real impact, but my influence also has great potential to change things.

As athletes, we have a platform. We have the power to use that platform to share the messages that are important to us. Often, we’ll use it to promote our sponsors. Choosing sponsors who share our values is crucial. I sincerely believe that partnering with sponsors who have a positive impact in their community is very important.

I recently had the opportunity to collaborate with Louelec, which offers an electric car subscription service for professionals and a private car-sharing service for businesses and communities (residences, universities, etc.). Not only does this partnership enable me to get around in an electric car (and to quantify the impact of this change thanks to WSP), but I also get to promote a local company that shares my values of sustainable development, collaboration, and eco-responsibility.

As I mentioned earlier, when it comes to transport, the general rule is to choose public transport (bus, train) whenever possible. When I must fly, I try to reduce the number of layovers.

I’ve also chosen to eat a mostly vegetarian diet, and I’d like to quantify the impact of this choice. We know that a vegetarian diet has a smaller carbon footprint than a carnivorous diet, which is one of the most significant ways one can reduce their carbon footprint as an individual.

I’ve also noticed that there are a lot of studies available online on quantifying carbon emissions from various sectors. Getting informed is the first step in the process, and there’s plenty of information available for everyone to educate themselves on the subject. Being informed means making better decisions!

What are the main challenges you’ve encountered on your journey towards carbon neutrality?

One of the constraints is that the most eco-responsible choice is not always the most financially or logistically accessible. It’s often a puzzle.

One of the main issues is that air travel consumes a lot of energy. As a consumer, it’s sometimes difficult to make an impact, but we can then go and see how the system works and see if we can do our bit to improve things.

I was lucky enough to partner with CAE, a Montreal-based aerospace engineering firm, my field of study, which aims to improve safety in the world of aviation. The use of technologies that limit the impact of the aeronautical industry on the environment contributes to this objective. Among other things, CAE produces flight simulators to enable pilots to train in virtual environments. I’m doing an internship with them and working on assessing their carbon footprint. The aim is to reduce the emissions of the aeronautical industry to reduce the footprint of consumers when they take a flight. It’s another way of making a difference.

Have you seen any changes in the way environmental issues are discussed in the world of sport?

We’re talking about it more and more. Maybe I’m biased because the more you get involved, the more you meet people who care about the issue, so the more you hear about it. Generally speaking, I see a lot of interest from different teams. An American skier wrote a letter to the FIS (International Ski Federation) asking for systemic changes.

Among the actions suggested is the establishment of a circuit of competitions which would reduce the frequency of air travel by having competitors complete all the European stages on the circuit at once, followed by the North American stages, rather than travelling back and forth between the two continents.

Winters are generally warmer, and it’s increasingly difficult to get enough snow to build our jump sites. The impact of climate change on the winter sports community is undeniable. Last year, the lack of snow forced our team to change locations for a training camp. Competitions take place on sites that are created partly with artificial snow, and sometimes entirely with artificial snow, as was the case at the last Olympic Games. We have a front-row seat to climate change because we spend our winters outdoors.

We have some very inspiring leaders in Quebec, such as Philippe Marquis. We’re creating a real culture.

Has this project given you other opportunities to take environmental action?

A lot more than I thought, and I’m really grateful. I joined the Athlete Alliance to Protect Our Winters (POW). POW is a national organization run by people who want to be solutions-oriented, creating a motivated and inspiring community.

I attended a lobbying event in Ottawa with them, where we presented a sustainable mobility project for access to Canada’s outdoors. I had the chance to speak to members of parliament about the scale of the problem and the solutions we were proposing. We need to make the outdoors accessible to the public so that people understand the importance of protecting it. Important changes come through politics. We’re fortunate to live in a country where citizens can express themselves, and we used this privilege to put forward what’s important to us.

I also took part in the Hot Planet Cool Athletes tour, visiting schools in Ontario to talk about climate change and the power we have as individuals. The aim is to help young people become aware of the situation and inspire them to take action.

I’ve also teamed up with Louelec and CAE, two sponsors whose values are aligned with mine and who found me through my carbon neutrality project with WSP.

Plus, I’m lucky enough to be a panellist for Green Sports Day on October 6!

What does it mean to you to have your efforts to become carbon neutral recognized by the IOC and to be nominated for an IOC Climate Action Award?

I was really touched. I love my sport and I dedicate a large part of my life to it. I do it out of passion and I love what it brings me. To be able to have an impact that’s bigger than my performance is something I really value. Using my passion to get involved in a community gives me a great sense of achievement. This nomination is recognition of those efforts. I devote a lot of time to my carbon neutrality project and it’s great to see my efforts recognized.

What positive impact has your involvement in this project had on your sporting career, those around you and your mental health?

I’d say the impact has been very positive. It’s the first time I’ve had a project other than my sport or studies in which I feel I’m making a difference in my own way. It’s very motivating. It inspires me to take action for what I believe in. It gives greater meaning to my sporting career.

Other athletes have reacted well to my project. I think that in the coming years, it will be easier and more intuitive for other athletes to draw inspiration from my project.