Reliving Canadian glory from the Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games

Whoever hits the podium for Team Canada at Tokyo 2020 will be building on a legacy that was established over a half-century ago.

Canadians claimed four medals at Tokyo 1964, the first time that the Olympic Games were held in the Japanese capital. And although the athletes all took unique paths, their journeys all ended in the same place: glory.

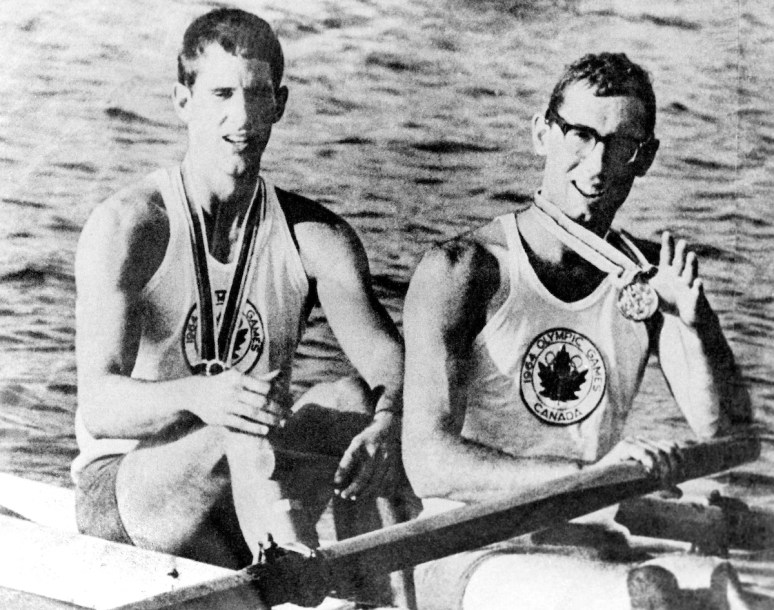

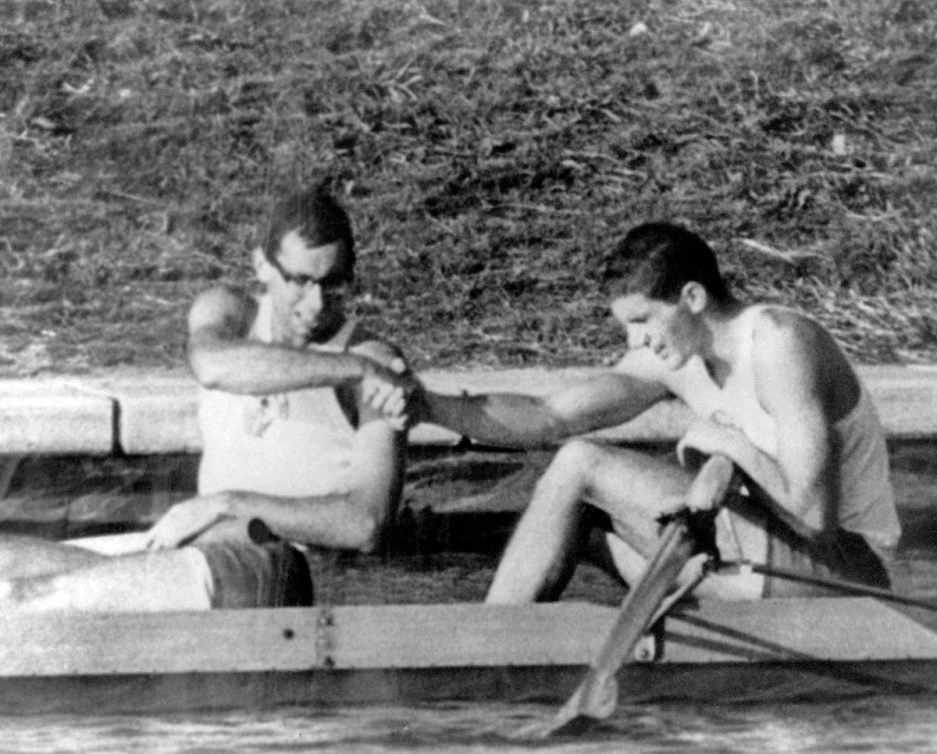

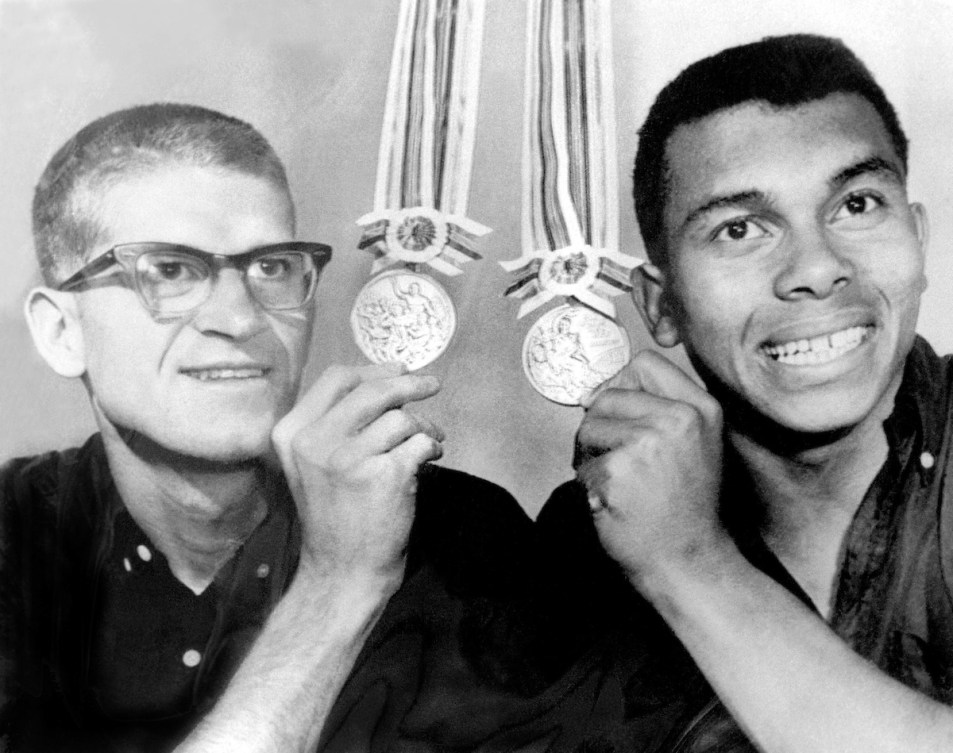

Roger Jackson and George Hungerford (rowing)

From a plan-shifting diagnosis to an unlikely pair of underdogs surprising the world with Olympic gold to glory.

Canada’s only gold medal at Tokyo 1964 came from a place that no one could have predicted: the pairing of Roger Jackson and George Hungerford.

In the summer of 1964, Hungerford came down with a case of mononucleosis that ruled him out of the men’s eight. Meanwhile, Jackson’s regular partner in the coxless pair was called upon to take Hungerford’s spot, leaving Jackson as an alternate heading to Tokyo.

But Hungerford wasn’t going to give up his Olympic dream. Despite having never rowed a pair before and still battling to recover from mono, he began exhausting training sessions with Jackson just weeks before the Games. They headed to Tokyo having never competed in a race together and with no real hope of reaching the podium.

Their natural chemistry, however, propelled them to a win in the first heat and qualification into the final. Still, not much was expected from the pair. The final came down to a photo finish and the Canadians, who had chosen to row without a rudder, came out on top. Dubbed the Golden Rejects, Jackson and Hungerford would go on to share that year’s Lou Marsh Award as Canada’s top athletes.

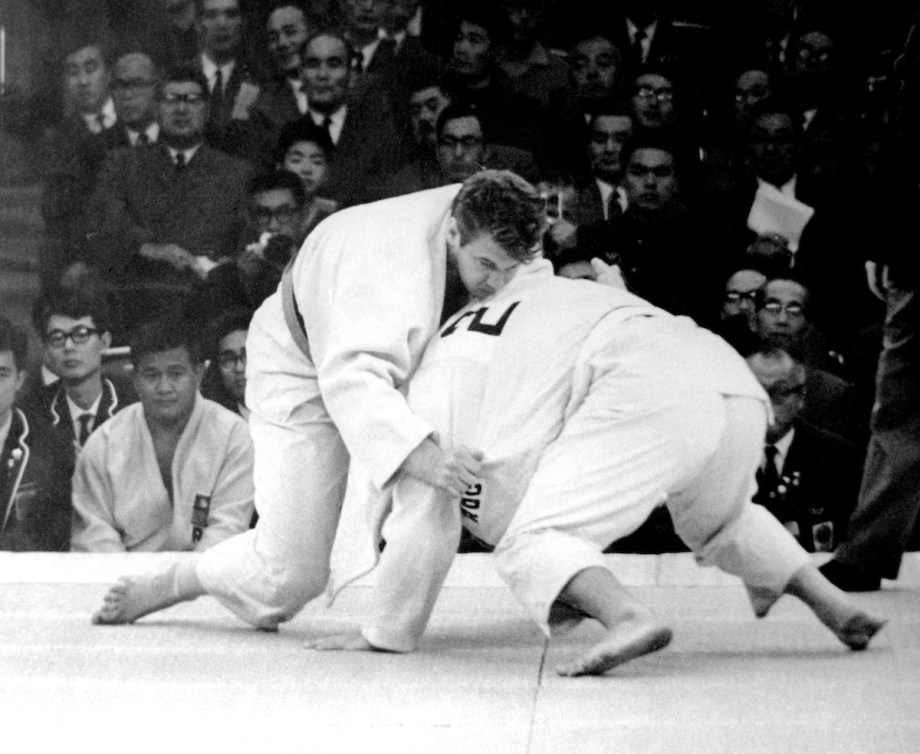

Doug Rogers (judo)

From the blue line to the dojo to a battle with a very familiar opponent to glory.

Though Doug Rogers‘ name is now closely associated with Canadian judo, his athletic career began in a different place: on the ice. In his youth, Rogers was a high-scoring defenceman whose team won the Ontario Minor Hockey Championships. But at 15, his passion shifted to judo. By 1960, at age 19, he’d moved to Japan to study at the renowned Kodokan Judo Institute.

Rogers spent years training with judokas in the sport’s ancestral home, including Isao Inokuma, a multi-time winner of the All-Japan Judo Championships. With judo added to the Olympic program at Tokyo 1964, the timing couldn’t have been more perfect for the Canadian.

In the heavyweight division, Rogers defeated three opponents to reach the final, in which he faced Inokuma. The Japanese competitor would come out with the gold, but Rogers’ silver medal was Canada’s first in judo.

Bill Crothers (athletics)

From a prodigious start on the track to the beginnings of a career as a pharmacist to Olympic success to glory.

If you live in Markham, Ontario, you might immediately recognize Bill Crothers‘ name from the pharmacy where he worked for years, or the high school bearing his name. But you may be less familiar with the athletic endeavours that brought him to prominence in the first place.

His was a classic case of a young person juggling academics and athletics. Both a top student and promising runner in high school, he earned a scholarship to the University of Toronto’s pharmacy program. Around the same time, he was running circles around his competition on the track; at one point, he held the Canadian record in all distances from the 400m to the 1500m.

But it was in the 800m that he’d reach the Olympic podium, earning a silver at Tokyo 1964. He would also compete at Mexico City 1968 before returning to Markham and putting his university education to good use.

Harry Jerome (athletics)

From a promising start in a variety of sports to a pair of devastating leg injuries to an Olympic comeback to glory.

Whether he was showing it on the baseball diamond, the football field or the soccer pitch, it was clear from an early age that Harry Jerome had some athletic gifts. But it was on the running track that he found his true calling.

At the 1960 National Championships, he equalled the standing world record in the 100m (10.0 seconds) and headed into Rome 1960 as a medal favourite. That dream was dashed, however, when he tore his hamstring in the Olympic semifinal. Two years later, at the 1962 Commonwealth Games, he suffered a torn quadriceps muscle that could have ended his career.

Despite being labelled a “quitter”, Jerome persisted and qualified for Tokyo 1964. In the 100m final, he posted a time of 10.25 seconds that earned him an Olympic bronze and set the stage for many memorable moments to come in Canadian track and field.