Mary Spencer inspires Indigenous youth to believe that nothing is impossible

WRITTEN BY BEV WAKE

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAVID JACKSON

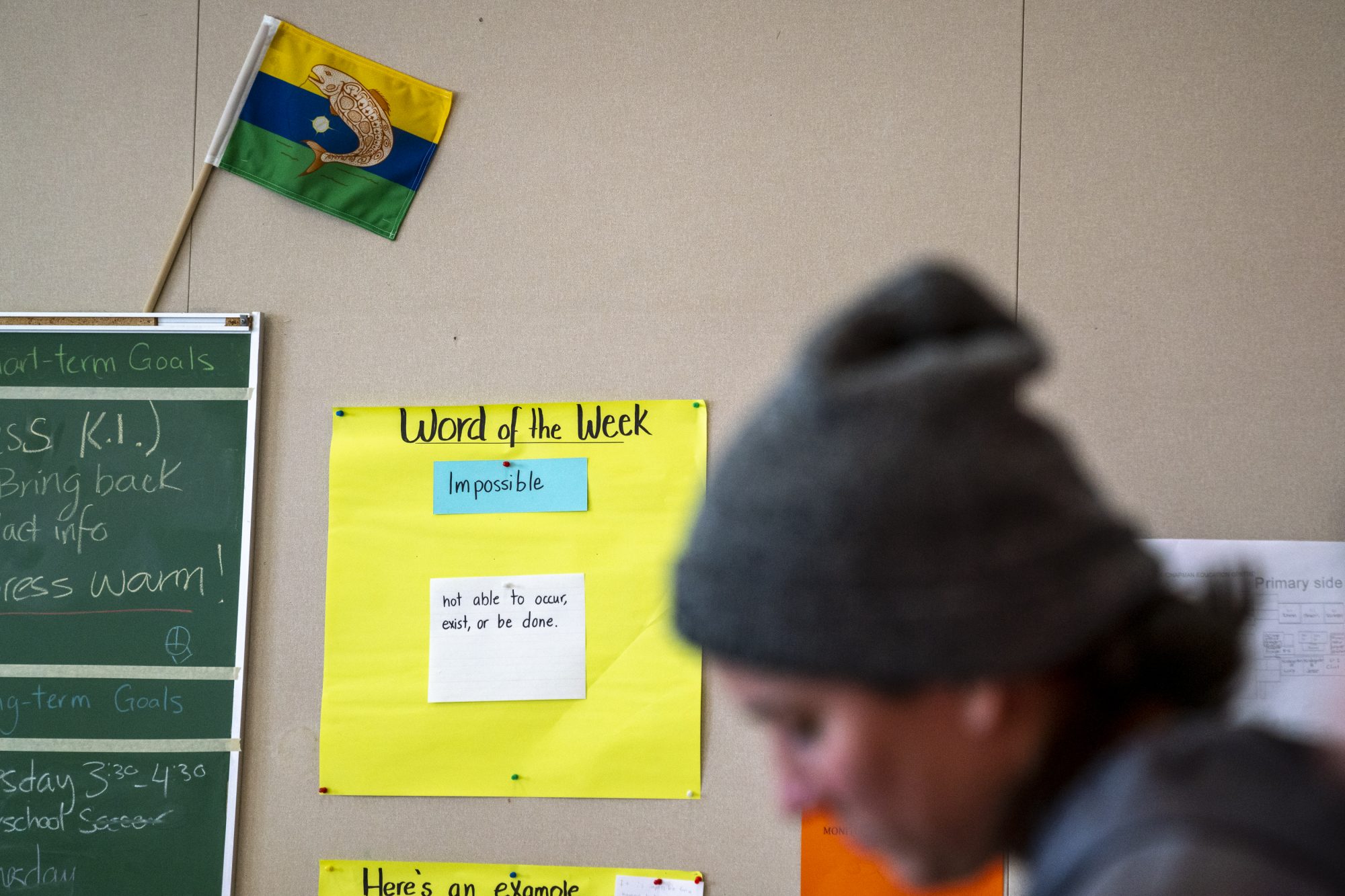

The word of the week is tacked to the classroom wall, the printing so perfect it could only have been written by an elementary school teacher: “Impossible”.

Beneath it, the definition: Not able to occur, exist or be done.

To Olympic boxer Mary Spencer, the word has no meaning.

And on a cold, blustery, fall day in 2019, in a small First Nations community in northern Ontario, Spencer wants the kids in the classroom to feel the same way.

Spencer is a three-time world champion and five-time Pan American champion. She tied for fifth at London 2012 when women’s boxing made its Olympic debut. At the time, her likeness could be seen on TVs and in magazines across the country as part of a CoverGirl advertising campaign.

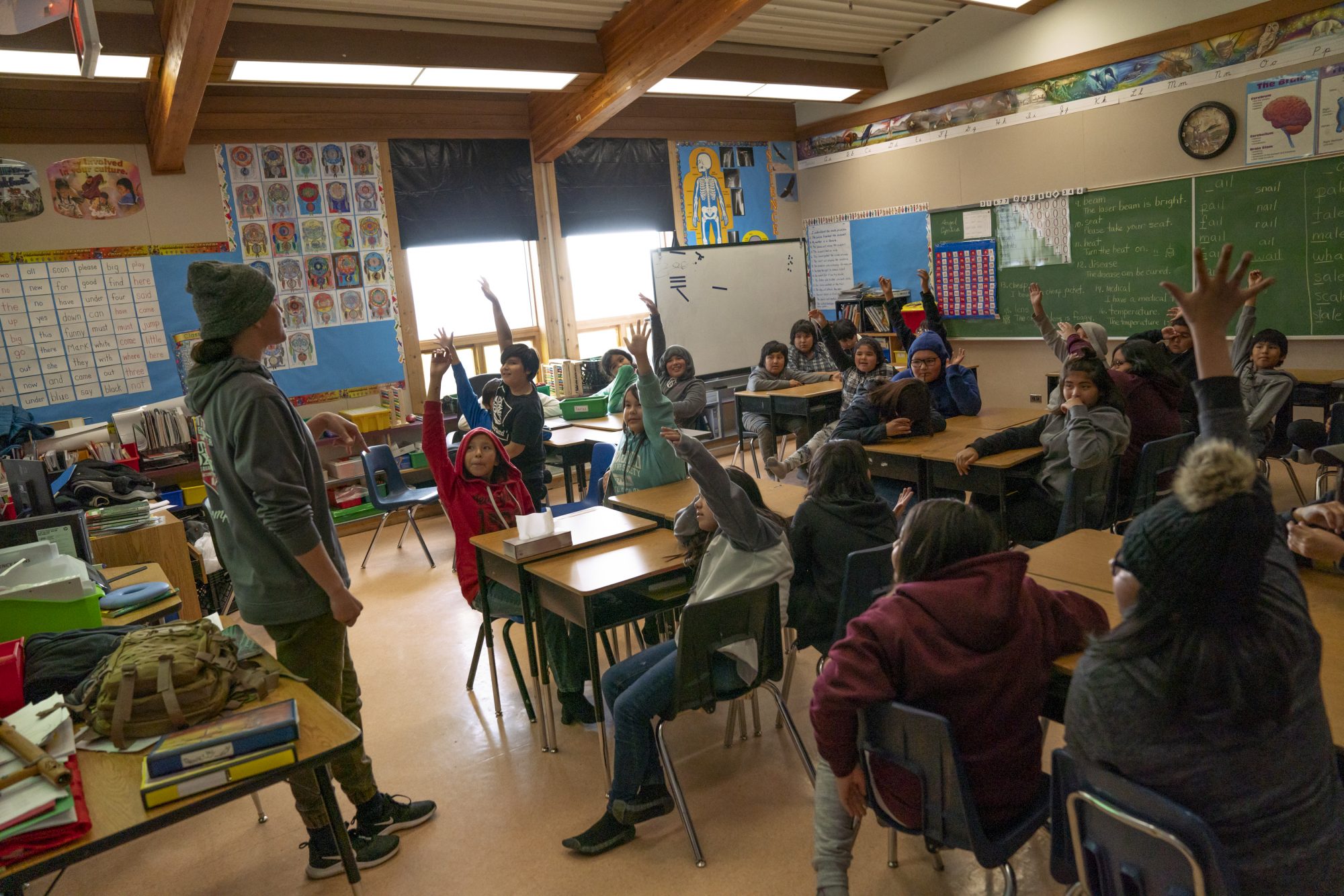

To the students in Grades 3 to 8 at Aglace Chapman Education Centre in Big Trout Lake — about 580km north of Thunder Bay and home to just over 1000 people — she’s a big deal.

Spencer remembers what it was like to be in their shoes: to doubt yourself, to see the word “impossible” on a wall and think it applies to you.

That’s why she tells them a story about her shoes.

She was their age, 11 or so, when she started playing basketball at school. All the other girls had really nice basketball shoes while hers had huge holes near the toes. When she asked for new ones, her mom said they couldn’t afford them.

Instead of giving up, Spencer thought about different ways she could make money. She looked for cans and bottles to return for deposits. She took grocery carts across parking lots for people too lazy to retrieve their quarter. While $120 seemed like a lot of money, eight quarters a day did not and two months later, she had what she needed to buy those shoes.

She went on to represent Ontario in basketball at the 2002 North American Indigenous Games.

There’s a lesson there, and the kids understand it.

“A goal of getting a pair of basketball shoes can be translated later on to a goal of going to the Olympics, because it’s the same thing,” says Spencer from her home in Montreal. “You have to have a clear vision of what it is you want. You have to understand what you need to do to get there and you have to be willing to put in the work to achieve those things.”

“Once you commit to the work that it’s going to take and you’re honest with yourself about what it’s going to take… then what can stop you?”

Instead of spending a few extra days with her family in Windsor over Thanksgiving, she got on a plane and flew to Toronto and on to Thunder Bay and Sioux Lookout in a 19-seater airplane before finally landing in Big Trout Lake, along with 20 boxes of takeout chicken flown in once a week for the fast food-deprived locals.

The journey took 15 hours. She was there for four days.

Spencer can be reserved, introspective. But put her in front of children and the stories flow. She relaxes, opening up completely. Her energy is contagious. Spencer knows how important it is to connect.

That’s why, even before her Olympian fame, she visited First Nations communities as part of Motivate Canada’s GEN 7 Aboriginal role model initiative. That’s why she quietly made monthly trips to the Cape Croker reserve near Wiarton, Ontario, where she was born.

It’s why the Canadian Association for the Advancement of Women and Sport and Physical Activity placed her on their Most Influential Women list in 2011. It’s why she would go on to receive a 2014 Indspire Award — for her accomplishments in sports and her work in the Indigenous community — and a 2017 meritorious service decoration from the Governor General.

And it’s also why the Canadian Olympic Committee has recognized her with its Randy Starkman Award, given to a national team athlete who uses sporting excellence for the benefit of the community.

Read The Olympic Life: Freedom fighter by Randy Starkman

Read Spencer continues Starkman legacy of helping children in need

“She was the glue for our entire youth group,” says Abbagayle Jones, who was one of the teenagers Spencer used to visit in Cape Croker, bringing cartons of boxing gear with her. “We need more of her in the world, that’s definitely so.”

For Spencer, the motivation is simple.

“When I first started boxing, once I got on the national team, I found myself in a better place than I was when I started as a teenager. I wanted to start going back to my roots and giving back,” she says.

”You hear all these issues and problems that are facing First Nations communities, and what do you do? Well, all you can do is bring your gifts, right? Bring your gifts and use them in a good way. And for me, it’s sport. That’s the gift that I have. And the only way I know how to use that in a good way is to share it with young people and teach them. That’s how I feel like I can contribute to communities.”

You can almost hear the smile on Spencer’s face as talks about Kashechewan, or Kash, as it’s called, and the boxing gym she’s started in the Cree First Nation on the eastern side of northern Ontario near James Bay.

She discovered Kash about two-and-a-half years ago, when her partner at the time applied for a teaching position and — because communities like Kash and Big Trout Lake struggle to find teachers — was offered the job a day later. Spencer went, too, thinking she could take some courses online and maybe coach basketball.

Through a friend in a neighbouring community, she ended up getting involved with a program designed to keep kids from getting in trouble, run by the Nishnawbe-Aski Legal Services. From there, she ended up branching into restorative justice — a role that has her flying to Kash about once a month.

The kids all asked her the same question: Why wasn’t she teaching boxing?

“I didn’t want to force boxing on them,” says Spencer, who took a boxing bag and three pairs of gloves with her when she moved. “It’s a sport where you kind of have to introduce it kind of slowly and gently because … there’s a lot of pushback towards a sport that some people view as violent.”

But others heard the question, too, and thought: Why not?

With some extra money left in their budget at the end of 2017, Nishnawbe-Aski Legal Services bought a boxing ring. Someone else found a clinic with space in the basement that wasn’t being used — locals believed it was haunted — and things developed from there.

Spencer reached out to Boxing Canada and Boxing Ontario and they sent up gloves and headgear. Spencer’s old gym in Windsor donated gloves and other equipment. Marnie McBean, a three-time Olympic gold medallist in rowing, provided a speed bag and more gloves.

The finishing touches — proper flooring, weights, cardio equipment — were made possible when Legal Services received a grant from Choose Life, a suicide prevention initiative that falls under Jordan’s Principle, designed to ensure First Nations children in Canada get the services and support they need.

Christine Head, a high school counselor in the community, says the facility fills a gap. “The gym has been getting used more and more the longer it stays open,” she says. “There were very few spaces to get not only physically healthy but emotionally healthy and mentally healthy before the gym opened.”

Spencer was inspired, in part, by former national boxing champion Kent Brown. A member of the Fisher River Cree Band in Winnipeg, Brown helped open a similar club in Cross Lake First Nation, about eight hours north of the Manitoba capital, in 2011.

“I went up with him a few times and saw how he was getting it started. It was really inspirational for me. He mentored a man who wanted to learn to be a coach and he helped them get equipment and find a place to build the gym,” says Spencer, who travelled to Kansas for a tournament with Brown and some of his Cross Lake athletes, including then-16-year-old Kenzie Wilson who won her event.

“She was 800 kilometres north of Winnipeg with no access to sport before Kent just decided to bring the sport he loved to this community,” Spencer says. “She actually came with her mom, who was dying of cancer. Her mom just wanted to see her compete in boxing, because she knew she loved boxing, and she won the whole tournament. When you see something like that, you just want to open up as many clubs as you can.”

When Brown first started working in Cross Lake in 2009 it was with the kids in mind. “The suicide rates in Cross Lake were astronomical. We wanted to figure out how, you know, we can engage these kids and talk about things like that.”

He’s seen the difference boxing can make.

“It gives them focus, discipline and living a healthy lifestyle, first of all,” he says. “And it gives them a venue to vent their anger and frustration. My whole thing is boxing saves lives. They may not compete ever, but boxing saves lives because it gives you that mental, emotional, physical and spiritual well-being.”

He believes Spencer can have the same impact in Kash.

“She is a phenomenal coach,” he says. “And you know, it’s great because it’s coming from a person who is an Olympian, still chasing after her dreams. When she comes into the gym, all the girls just get inspired and just want to be like her.”

Spencer thinks about it sometimes, about what her life would have been like if she hadn’t found a way to raise money for those basketball shoes. If she hadn’t walked into the Windsor Boxing Club and asked them to teach her to fight, undeterred by her father’s words six years earlier that “boxing isn’t for girls”.

She wonders what would have happened if her family had stayed in Cape Croker. Her father had been happy there, working as a minister, but her Chicago-raised mother was not. There wasn’t even running water.

“I would have gone through grade school and high school and all those years where I got to learn all these different sports. I was 16 years old when I finally walked into a boxing club, and I was able to be coached by a four-time Olympic coach. I wouldn’t have had any of that,” she says.

“When I go to these reserves and do sports, a lot of these basic drills that I’m doing, kids have never even done them. Even basketball or soccer, sports that you do all the time in gym class, they’re sometimes brand new to these kids. I just thought, wow, my life would be completely different without sport.”

Jones, who now lives in London, Ontario, says her life would be completely different if Spencer hadn’t made those monthly visits to Cape Croker. “I probably wouldn’t have moved to the city if it wasn’t for Mary. She inspired me to do what I wanted to do. She told us we can’t have it unless we go out and get it.”

Wherever the dreams of the youth she encounters may take them, she wants them to dream big. To set goals. To work to achieve them.

Impossible? They need to forget they ever saw the word.

— With files from David Jackson in Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug

This article has been edited since its initial publication