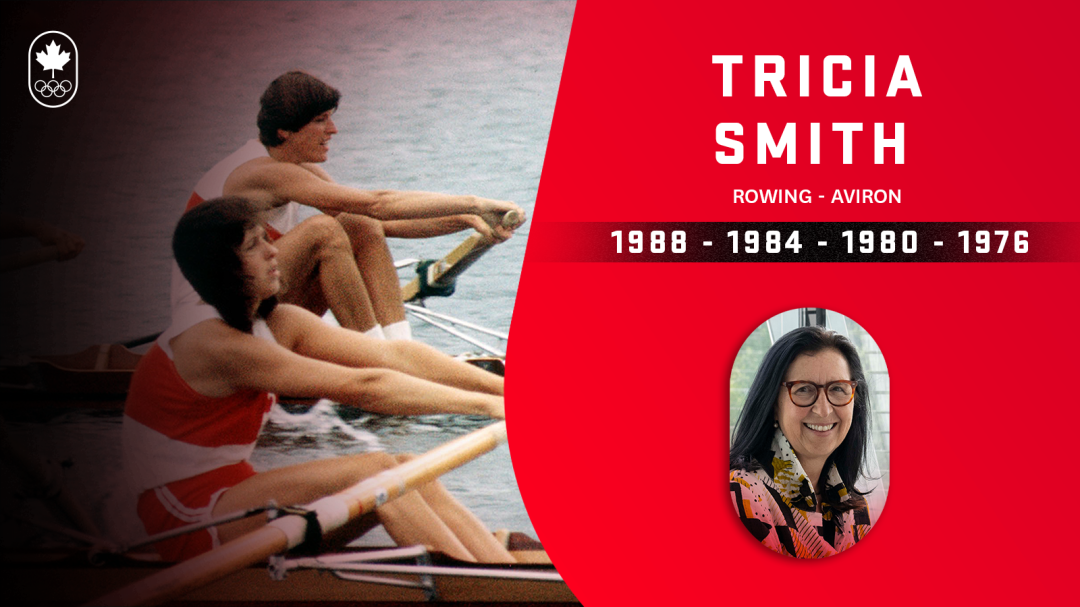

Team Behind the Team: The journey of Tricia Smith, from four-time Olympian in rowing to COC President

The Canadian Olympic Committee (COC) is proud to put athletes at the heart of everything it does. At all levels of our organization, from our Board of Directors to our interns, our team is comprised of people who truly believe in the power of sport – including an impressive group of Olympians, Paralympians, Pan American Games athletes, former national team athletes, rec league athletes, and passionate sport lovers. In this series, we’ll share stories from members of our team who have competed at major multi-sport Games and who are now dedicating their professional lives to helping the next generation of Team Canada athletes live their dreams.

Tricia Smith is a four-time Olympian whose career highlights include a silver medal at the Los Angeles 1984 Olympics, seven World Championship medals and a Commonwealth Games gold.

A lawyer, Smith was elected to be a member of the IOC in 2016 and has won numerous awards including the Order of Canada. She has been a volunteer in sport for more than 40 years starting in 1980 as a member of the first COC Athletes’ Council. Smith is currently President of the COC, Vice President of World Rowing, Board Member of the Council of Arbitration for Sport, and Executive Committee Member of both the Association of National Olympic Committees and of Panam Sports.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

What role did sport and your athletic family play in who you are today?

I was really fortunate to grow up in a family of five kids with parents who had been athletes, and who made sport a part of our lives.

My parents met in the gym at the University of British Columbia. My mom represented Canada at the Pan Am Games in basketball and my dad was a star university rugby player. They were young, active parents, and we kids were just as active along with them. We were made to feel that there was nothing we couldn’t handle – whether it was being towed on skis, holding onto water ski ropes behind the station wagon on a rare Vancouver snow day, playing neighbourhood scrub games on summer evenings, or learning to waterski along with all the neighbourhood kids behind a ski boat, which I think might have been built from a kit. My parents must have had a lot of energy! I saw them always step up in volunteer roles as well, largely in sport.

We all swam competitively at some point. I don’t remember how we started but [it was] probably a good idea living next to the beach. Shannon, the youngest by four years, was by far the best. At age 14 she won a bronze medal at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. I was so proud of her.

So, idyllic beginnings?

For sure. And like many families, we also had some misfortune. We lost my brilliant mom in her early 50s to a rare brain disease and around the same time, my father had surgery to remove a disc. It was a pretty common surgery in those days but in the process the surgeon damaged his nerve and my dad lost the use of his legs. Then we lost both my brothers–Jeff in a motorcycle accident and Dean, almost exactly seven years later, in an avalanche. Both were talented, kind, and intelligent young men. Jeff was also a lawyer and he and I definitely shared the same sense of humour. Dean was a bush pilot, our guide in the mountains or on the sailboat he built.

Losing them was obviously more than devastating, as if the wind was knocked out of you, and along with the challenges faced by my parents, for me, it truly put things into perspective. It made me appreciate what I had had, and what I still had. Not everyone is so fortunate. It also put things into perspective in terms of what matters.Bad things happen in this life, situations which are out of your control, but you can decide what to do next.

For me I think that has translated into not wasting time or energy on adding to the negative, and trying to give back in areas where I think I can make a difference. I’d like every kid to have opportunities like I did, to be made to feel anything is possible if you put your mind to it.

I learned so much through sport, got my education, have had opportunities to work with exceptional people, domestically and internationally, and to create opportunities for young people where they might not have otherwise had them. I have had seats at decision-making tables in something I believe can actually make the world better.

You went to four Olympics. What are some of the highlights?

There are many but I will mention three.

Firstly, seeing my little sister win that medal at the Olympics in 1976. On reflection it was even more impressive in that she and others were competing against the dominant East German team, who we now know were part of their state sponsored doping program. In addition, support for our athletes at the Games in those days was really hit or miss. Even though she was only 14 years old and something like top 10 in the world in 5 events, her coach wasn’t selected, so he wasn’t even allowed to be with her for support, and there were no cell phones in those days. We can always do better, but I am thankful that things have changed for our athletes and coaches, in a positive way.

Secondly, I will never forget the roar of the home crowd when we marched into the stadium as Team Canada at the first Olympic Opening Ceremony I attended in Montreal.

And finally, the time my pair rowing partner and I spent training in Italy with our coach for two seasons prior to the 1984 Olympics. As we were top 3 in the world, we were “A” carded and qualified for something like an extra $1500 for the year for special projects. Our special project was buying tickets to Italy after our coach, with no professional positions in Canada, took a job with the Italians.

The first year he let us use his apartment and the second year we found our own. We traveled to all the season’s regattas on the bus with the Italians. They lent us a boat and bicycles, and our coach lent us his car when we needed to go to town for groceries. We were always on the podium at the season’s events and the World Championships. We worked incredibly hard, it was a lot of fun, and I was really proud of what we were able to accomplish on our own, with amazing support from our coach and the international community of rowing. I am still very close to our Italian friends from that time and the next generation of my family are friends with the next generation of theirs.

You were involved in the first Athletes’ Council for the Canadian Olympic Association (as it was called at the time) which emerged right before the 1980 boycott. Tell us the impact that had on you?

Athlete representatives from every sport were invited for the first time, to a meeting with the Canadian Olympic Association. Very few sports had athletes’ committees in those days. I had been one of the two rowers who started an AC in rowing, so that may have been why I was chosen.

We were asked what we thought about a possible boycott. I can’t say we were given a lot of choice.This was in the time of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. Russia had invaded Afghanistan and we were told that the world had to collectively stand up to this threat and aggression. We were disappointed of course but the general feeling was that if we were being asked to do our part, then we should do our part. So, Canada went along with the boycott.

Later, I came to understand how naïve we had been and that we had essentially been used. Very little was done by others. Trade continued; exchanges continued. The sport boycott accomplished nothing. In fact, when I got back to university in the Fall, someone even asked me how we had done at the Games. That was a huge lesson. It sounds cliché but it is true that there is great power in sport but its value and unique power comes from engaging, not disengaging, bringing people together and building those essential bridges, not in building walls. I have seen more positive change from that approach than from any boycott.

You have volunteered for more than 40 years in sport including as Vice President of World Rowing. Tell us about the work you did there with respect to gender equity.

Many things! It was a long process, so I’ll mention a few which were particularly key.

First, when I became Chair of the Women’s Commission, I was able to lead a change in structure so that the members of the Women’s Commission came from all the other World Rowing Commissions. That created a dynamic of integration, whereby issues previously categorized as “women’s issues” were World Rowing issues, and no longer marginalized as the work of one commission. So, for example, identifying why there were so few female umpires and developing strategies to address this became the job of the Umpires Commission, not the Women’s Commission. Medical issues specifically affecting women became the job of the Medical Commission. Developing a balanced competitive program, the role of the Competition Commission, and so on.

We also ensured that qualified women were aware of and provided the opportunity to be on the pathway to leadership. This ultimately resulted in election of women to leadership in Council and Council becoming gender balanced. We also commissioned a study of the history of women in the sport so we had a clearer understanding of how certain structures had developed and, if needed, how they could be addressed. We gathered data to show where we were, our strengths and weaknesses and identified ways to progress, including rule changes where necessary, and then measured and supported the changes with data.

I have seen Minutes of World Rowing (FISA at the time) which document discussions about the belief that rowing could negatively affect women’s ability to bear children. When I first started, there were few women in leadership, women were still racing half the men’s distance and there were fewer women’s events. The Council is now gender balanced and women’s and men’s events and distances are the same. We built the foundation for those changes.

What do you think you bring into the role as President of the Canadian Olympic Committee as an Olympian?

I had not thought about being President of the Canadian Olympic Committee until one of the board members pushed me to think about it. I thought I had enough on my plate with my other volunteer roles and in building a business. I didn’t really see myself in such a role. In the end, I was convinced I could contribute. I feel very fortunate to be President of the COC.

Obviously, being an Olympic athlete is valuable for this role. I was an Olympic athlete many years ago, so a lot has changed, but I hope I can still relate. I understand that an athlete has to be creative in order to be the best they can be, often with extremely limited resources. I understand the importance and relationship between the various players in the sport system.

This understanding helps ensure we set the right priorities to do what we can to support the athletes, coaches, and the system in the best way possible. If you’ve been through it, you get it. It probably gives me some credibility as well as the leader of the COC Board. People do light up when you tell them you are an Olympian.

I have also brought to the role, as importantly, my legal training and background as well as my experience in building a successful business over the last almost 30 years. I have to say, since retiring from my paid job, the volunteer part of my life is even more enjoyable. I am no longer constantly a little bit behind on everything!

When you took over as President of the COC in 2015, the organization was dealing with a tumultuous situation with complaints about a toxic culture among leadership. What was that like for you?

It was very challenging, for sure.

In taking over as President at that time, I believed I could help address various issues. I remember I was working till midnight or later every day, between the COC and my professional job, but I never resented a moment of it because I could see a clear path to making things better. We commissioned an independent investigation and implemented every recommendation, many of which related to better governance practices. I do believe that almost any issue or problem in sport, and in many things, can be traced back to poor governance. That is why it is so important to get that right.

It is one of the things I’m most proud of in terms of what we did to turn the ship around after such a devastating loss of confidence by the Canadian public.

At various multi-sport games, you often go from event to event as one of Team Canada’s biggest cheerleaders. Why is that so important for you?

I remember competing at major events, usually far from home, and rowing out to the start line, and how wonderful it was to hear someone say, “Go Canada!” In fact, it was so unusual that I remember one time even saying to my rowing partner “Who is that?!”.

Hearing “Go Canada!” or seeing the flag, I know what a difference it made for me. That’s why I always try to do that for our athletes. Plus, who wouldn’t want to go and see our amazing athletes? It is always a privilege. Cheering is easy.